US superiority over Iran is obvious, the endgame is not

The real question is not whether the United States can destroy Iran’s capabilities, but whether it can end the Islamic Republic—and control what follows.

The real question is not whether the United States can destroy Iran’s capabilities, but whether it can end the Islamic Republic—and control what follows.

As President Trump weighs options against Iran, he faces a legacy‑defining choice that could reshape the century, with the Islamic Republic at its most precarious moment since 1979 after years of US pressure and a determined popular uprising.

The killings that swept Iran last month revived memories of 1988, when the Islamic Republic erased thousands of political prisoners in silence—my brother, Bijan, among them.

The Islamic Republic was bad news in 1979 and it is bad news in 2026, sending security forces to beat and murder peaceful protesters. Deporting Iranians to a country gripped by violent repression is hardly the ‘help’ the United States promised.

Israelis and Iranians have been cast as enemies for so long, but during Iran’s uprisings their voices tell a different story as Iranians drew a line between themselves and the Islamic Republic.

As Iran’s authorities impose silence through violence and disconnection, what the world is witnessing is not unrest but defiance at its most basic—people refusing to disappear, to be reduced to numbers, or to surrender their names.

Iran’s near-total internet blackout since January 8 did not only shut down social media but collapsed the country’s last channels to the outside world, isolating families and sharply limiting what evidence of the crackdown could escape.

The latest wave of protests in Iran once more demonstrated both the depth of popular opposition to the Islamic Republic and the limits of mass mobilization in the absence of a decisive breakdown in the regime’s coercive capacity.

What happened in Iran on Thursday night was not simply another protest. Coordinated mass demonstrations unfolded nationwide in response to a direct call from Prince Reza Pahlavi that specified not only the action but also the timing.

Three days after merchants ignited strikes across Iran, the country’s bazaar is now openly defying the Islamic Republic, marking a historic break between conservative traders and a state accused of sacrificing livelihoods to missiles and security spending.

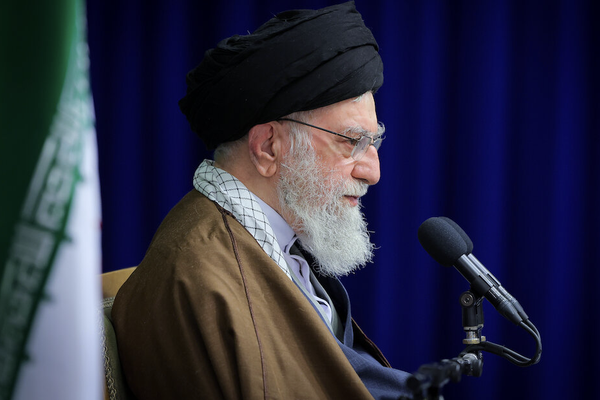

Free speech. Open dialogue. People having access to one another, the ordinary ability to speak freely and exchange ideas. These might be the downfall of the system patiently built up by Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, not foreign weapons.

Power politics in Tehran has reached a stage where even the most routine public affairs—a film festival, an environmental report or the World Cup draw—spiral into controversy, as if the system cannot tolerate anything resembling normalcy.

In Iran today, the riskiest act is neither protest nor journalism. It's conversation.

Iran held large-scale state funerals this week for unidentified soldiers from the 1980s war with Iraq, nearly six months after its 12-day clash with Israel, and amid deepening public distrust fueled by ongoing security, economic, and environmental crises.

At eleven o’clock each night, Tehran time, my studio, half a world away, seems to inherit the city’s fatigue. The callers gather like silhouettes behind a scrim of static.

The privileged children of Iran’s ruling elite are building futures overseas that their parents have withheld from millions of Iranians for almost half a century.

Six years after Iran’s blackout and mass killings, two women keep alive the month the Islamic Republic tried to bury.

At dawn on a November morning in Ahvaz, a city in Iran’s oil-rich southwest, municipal enforcers arrived at Zeytun Park to demolish a small food kiosk that had sustained one family for more than two decades.

In Iran, privilege often dresses itself as virtue, with the best-known example being a former vice president’s son boasting about his “good genes”—a phrase now firmly embedded in the national lexicon.

It’s eleven o’clock at night in Tehran when I open the phone lines for my live call-in show, The Program. Friday night is when I ask Iranians to do something that has become almost subversive: not just to talk, but to listen.

It was eleven o’clock at night in Tehran when I opened the phone lines for my live program from Washington. It was the middle of June and Iran was under Israeli fire: calls flooded in from around the country.

It begins with a sound. A hiss, then silence. A man in Tehran holds his phone to a dry faucet at midnight; you can hear the air whistling through the pipes. “It’s 11:40 p.m. and there’s a smell of fire,” he says.