Young Iranians turn ancient bonfire festival into night of defiance

The Islamic Republic’s crackdown over the years has gradually turned the ancient festival of lighting bonfires before Nowruz into a night of youth defying authorities.

The Islamic Republic’s crackdown over the years has gradually turned the ancient festival of lighting bonfires before Nowruz into a night of youth defying authorities.

Despite its evolving nature, the festival of Charshanbeh Suri remains a deeply rooted cultural event—one that continues to reflect both the resilience of tradition and the defiance of Iran’s youth.

Traditional Charshanbeh Suri celebrations

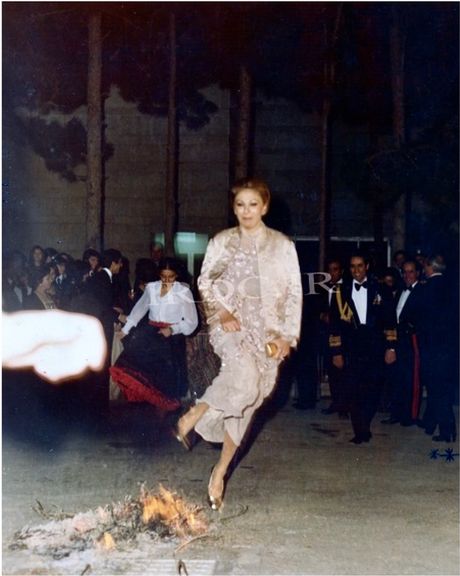

Charshanbeh Suri is celebrated on the eve of the last Wednesday before Nowrouz (Norouz), the Iranian New Year, which falls on the Spring Equinox (March 20 or 21). Chaharshanbeh means Wednesday and hence the name of the festival.

People normally light seven small brushwood bonfires in the streets or courtyards of their homes after sunset, jumping over them while chanting “May your red glow be mine and my pallor yours!”

Customs vary across the country but often include door-to-door spoon-banging in disguise for treats, fortune-telling, candle lighting, and traditional games. In smaller cities and rural areas, these traditions remain central to the festival, often accompanied by special dinners featuring local cuisine.

Suppression backfires

Following the Islamic Revolution of 1979, the religious establishment, which disdains ancient Iranian festivals as un-Islamic, imposed an unwritten ban on Charshanbeh Suri due to its association with fire, which they assumed to be a Zoroastrian tradition.

Islamic Revolutionary Committees -- incorporated into the police force a few years later -- soon began cracking down on youth celebrating with bonfires and firecrackers, particularly in major cities like Tehran. However, the more authorities attempted to suppress the festivities, the larger and more defiant the celebrations became.

Banning the sale of firecrackers led to the rise of homemade explosives, often resulting in casualties. Safe firecrackers and fireworks are no longer banned, but homemade variants to make greater noise still claims yearly casualties. In 2022, for instance, 19 died and 2,800 were injured during the celebrations. This year, according to Emergency Medical Services Organization, six have died and 50 have sustained serious limb injuries in the past few days, as celebrations began ahead of March 18, the eve of the festivities.

The police and the Basij militia of the Revolutionary Guards are mobilized annually to suppress gatherings involving large bonfires, loud music, and dancing. Clashes frequently occur, with youth taunting security forces through chants and fireworks.

Some neighborhoods, such as Ekbatan in western Tehran, have become hotspots for large-scale celebrations. The morning after often resembles a battle zone, with smoke from fireworks and homemade “bombs” lingering in the air.

In politically charged years—such as after the Green Movement protests of 2009 and the 2022 Woman, Life, Freedom protests—Charshanbeh Suri has taken on an overtly political tone, with participants chanting anti-government slogans in Tehran and other cities.

This year, Charshanbeh Suri coincides with Ramadan. On Saturday, Iran’s Acting Police Commander issued a categorical warning against “disregard for [Islamic] norms” during the festivities and the New Year holidays.

The name and origins of the festival

There is no evidence of fire-jumping traditions in pre-Islamic Persia. Zoroastrians, who hold fire sacred, would not defile it by jumping over it. However, they did light rooftop fires five days before the New Year to guide the spirits of the dead home for a reunion with their families.

Islamic-era historians have documented widespread celebrations among commoners and at royal courts over the centuries.

Most scholars agree that the celebration on the eve of the last Wednesday of the year is related to the Mesopotamian belief in the inauspiciousness of Wednesday, the fifth day of the seven-day week in the Babylonian calendar later adopted by the Jews who were held captive by them after the siege of Jerusalem in 597 BCE.