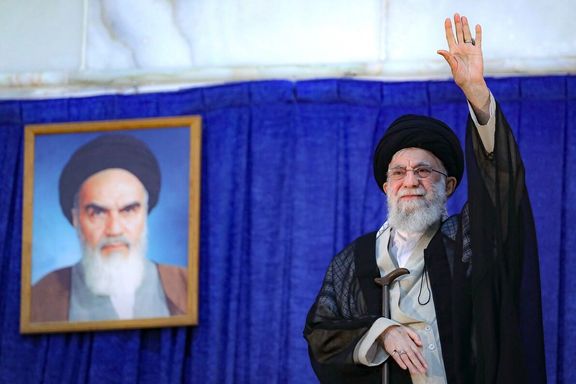

The portraits, to be clear, are those of Iran’s current and former supreme leaders. I’m leaving out their names because to my niece, they are one and the same. Not just them, but all the turbaned guys. And not just to her, but to most in her generation.

We, the so-called Millennials, fought the Islamic Republic. Iran’s Generation Z has disentangled itself from it. It has no time for it, lives in a parallel reality almost, detached from all that the state stands for and promotes.

A few weeks ago, a short video went viral of young girls struggling to name the Islamic Republic’s late and living leadership by their image.

The video was clipped from an apparently state-commissioned documentary aiming to illustrate the corrupting effects of so-called cultural invasion and rally those who care about revolutionary values.

Only, it did the exact opposite.

The image of teenagers giggling as they fail to identify the leaders underscored the proposition, often dismissed as wishful rhetoric, that the aging Islamic Republic will not survive the spice and sass of Iran’s generation Z.

The documentary, whatever its aim, showcased the profound disconnect between Iran’s rulers and its youth. What it also showed was how effortlessly cool the latter are about it.

“We cannot care less,” the girls’ body language seemed to say. “We really don’t,” my niece confirms this when I put this idea to her.

For those of us who grew up in the early years of the Islamic Republic, the contrast is striking. Not only did we know—and fear—our rulers, but we chanted and prayed for their health every morning at school.

We were steeped in propaganda, with little exposure to the outside world. The state broadcaster was the only show in town. Today, most homes have satellite TV, even though it’s illegal. And most teenagers are on social media, even though many platforms are filtered.

This access to all that’s out there has transformed Iran from within and below, even if the shell and the top remain the same. In her attitude toward religion and authority, my niece has much more in common with a teenager in the United States than she has with her mother.

I have a home video of my older brother’s birthday party from the mid-1980s, discovered in a house move and digitized a few years ago. Uncles, aunties and cousins dance to an Iranian pop song.

As they move about, a framed picture on a shelf at the other end of the room emerges and vanishes behind them: an A4 print of Iran’s then supreme leader, Ruhollah Khomeini.

The contrast boggles the mind today. But at the time it was all but typical. A time when millions had a portrait of this or that cleric at home, when respect and affection for the turbaned guys was still there—waning, of course, as men in uniform stormed houses and arrested partying aunties and uncles.

Over the years, injustice and repression eroded affection and erased all such individual displays of respect. The leaders’ images are still ubiquitous, but only in public and only sponsored by the state.

My niece and her friends have never really looked at these images. They do not examine Khomeini’s face on banknotes the way we once did, trying to find the fox that was said to have been hidden in his beard by the cheeky designer.

“You must be kidding me,” my niece told me when she caught me watching a presidential debate on state-TV last summer. “Who gives a crap about elections?”

A few words later, I learned she did not even know how many were running, let alone their names.

Unlike my generation, who believed in change through the ballot box, whose priority was politics and the collective, my niece’s generation is concerned with the individual: my hair, my rights, my aspirations.

The apathy with politics and the focus on self runs deeper and broader than the teenage folk, of course. But theirs is more natural, unforced—organic perhaps. And our generation can take some credit for that.

My sister is not my mother. Her daughter, my niece, has been hearing her swearing at Iran’s officials since she was a fetus. She has not been forced by my sister to “beware and behave.” She has not been scolded for getting a low grade in Religion at school.

My sister and I were suppressed both by the state and by our parents’ fear of the state. My niece has grown up with parents not just disillusioned by but vocal against the state. Little surprise then that she is bolder almost to the point of brashness.

“What does it have to do with my mom or her mom or their dear God,” my niece says when I meekly suggest that my sister may be uncomfortable with her outfit. “It’s not like I’m asking her to dress like this, is it?”

The near-intrinsic boldness at home has left its mark on the streets as well. Just look at the leading role teenagers played in Iran’s 2022 uprising. They fought harder than their parents, not over censorship or election fraud, but for their right to live.

It was a collective of struggles for the individual. And it triumphed in the sense that it normalized uncovered hair, the very thing that had a young woman killed, sparking the widespread protest aptly called the Woman Life Freedom movement.

So our turbaned leaders may still be watching over my niece. But they’re as relevant to her life as their framed pictures are to the music that fills the concert hall she entered for the first time with me.

I still do tell her about the fights of my generation, our campaign, for instance, to gather a million signatures demanding an end to discrimination against women in Iran. She nods approvingly but you can tell she’s unimpressed.

“Why bother shouting 'leave me alone' when you can just walk away,” she lectures me. Like many of her ilk, she appears to have stopped worrying about freedom and just lives it.