Assad’s ouster carries implications not just for Syria, which may now become a battleground for new proxy wars between regional powers, but for the broader Middle East, where the ripples of the fall in Damascus will be felt.

The new reality in Syria bears most heavily upon the Islamic Republic of Iran and its armed allies in the region. Assad’s downfall has disrupted the connections between Tehran, the Shia militia in Iraq, and Hezbollah in Lebanon.

A refashioned Middle East

Hezbollah’s ill-judged assault on October 8, 2023, opening a second front against Israel, hurled Iran into an unenviable strategic and financial position. Supreme Leader Khamenei wagered that Hezbollah’s arsenal might stall Israel and compel it to negotiate a ceasefire with Hamas as families of hostages led anti-Netanyahu protests. But Israel pursued its objective of dismantling Hamas and Hezbollah, the human costs in Gaza and southern Lebanon notwithstanding.

The costs for Iran were staggering as well: tens of billions of dollars invested over 30 years to build its much-hailed Axis of Resistance vanished in a single year.

Following Saddam’s ousting in 2003, Iran secured routes through Iraq and Syria, fuelling Hezbollah’s 2006 war effort. Yet Israeli strikes from July to October 2024 wiped out most of Hezbollah and Hamas’s leadership. In late October, Israel targeted several military sites in Iran, asserting that it had destroyed the country’s air defences. By November, Tehran had lost the ability to shield Assad and had to accept his defeat.

In Lebanon, Hezbollah’s diminished role has created opportunities for other political forces to reclaim influence. And in Iraq, Shia factions feel the heat as Tehran’s regional grip weaken and Ayatollah Sistani, Iraq’s most influential cleric, denounces the undue power of armed militias over the state. An anti-Iranian resurgence, once unthinkable, now emerges as a distinct possibility.

Shadow of uprising over Iran

Khamenei’s response to these setbacks was notably subdued. On December 11, 2024, he avoided mentioning Syria’s dominant faction, Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), or its leader, Jolani. Instead, he predicted that Syria would descend into an insurgency similar to post-Saddam Iraq. This cryptic pronouncement suggests a possible strategy to exploit instability in an attempt to reclaim lost ground and restore Iran’s waning influence.

The shadow of the widespread protests in 2022 looms ominously over Tehran. Warnings against popular uprising by senior figures, including the supreme leader himself, underscores the theocracy’s unease. Khamenei’s words betray not strength, but fear.

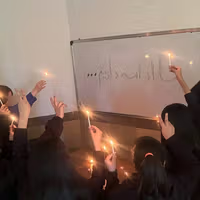

On December 12, 2024, Netanyahu addressed the Iranian people directly— for a third time in about three months—urging them to seize the opportunity presented by Assad’s collapse. Most remarkable, perhaps, was his attempt to invoke the mantra of the 2022 uprising in Persian: “Zan, Zendegi, Azadi,” he said, Woman, Life, Freedom, which excited and repelled Iranians on social media.

Middle East peace now hinges upon Syria

Since 2012, Syria has been the stage where regional and global powers collided—America, Russia, and three coalitions: Iran and Hezbollah, Turkey, and the Persian Gulf Arab monarchies led by Saudi Arabia. United briefly against ISIS, the terror group’s decline by 2022 restored the old rivalries. Turkey, under Erdoğan, played a deft and dangerous hand, juggling conflicts with Assad, ISIS, and the Kurds, all while reviving Ottoman-like aspirations for regional dominance.

Israel’s operations against Hezbollah and Iran have shifted the balance of power and inadvertently bolstered Turkey’s ambitions. Netanyahu’s decisions, with President Biden’s support, inflicted untold suffering on Palestinians and led to an unprecedented case against Israel at the International Court of Justice. But it also tore at the Islamic Republic’s fragile Shia imperium. Khamenei’s decades-long gamble, pouring Iran’s treasure into regional ambitions since 1989, now imperils his rule.

At the beginning of 2025, Turkey and its Arab counterparts have an historic opportunity to forge a new Middle East. Erdoğan, ever wary of Israel but keen to grasp the moment, wielded Turkish intelligence to enable HTS to topple Assad. President-elect Trump described the events in Syria as an “unfriendly takeover” by Turkey, signalling apprehension over Ankara’s ambitions. But Turkey alone cannot rebuild Syria and manage the return of millions of refugees. That may require a concert of will and treasure from Saudi Arabia and the Emirates.

At this pivotal moment, regional powers must avoid focusing solely on resolving the Israel-Palestine conflict. A coordinated effort to rebuild Syria could transform the region’s fortunes. Syria under Jolani is unlikely to move toward normalization with Israel. Still, it defies belief that millions of returning refugees would yearn for renewed conflict.

These war-weary souls seek not battle, but the quiet dignity of rebuilding their homes and lives. A bold, visionary effort to uplift Syria could transform the fortunes of the region's most grievously afflicted—Syrians, Lebanese, and Palestinians alike. As for Iran, the gamble executed by Khamenei and his IRGC commanders seems to have backfired, leaving them in their most precarious position in recent memory.